Chapter 4 - Popayan (the White City) and Ipiales (Sanctuary of Las Lajas)

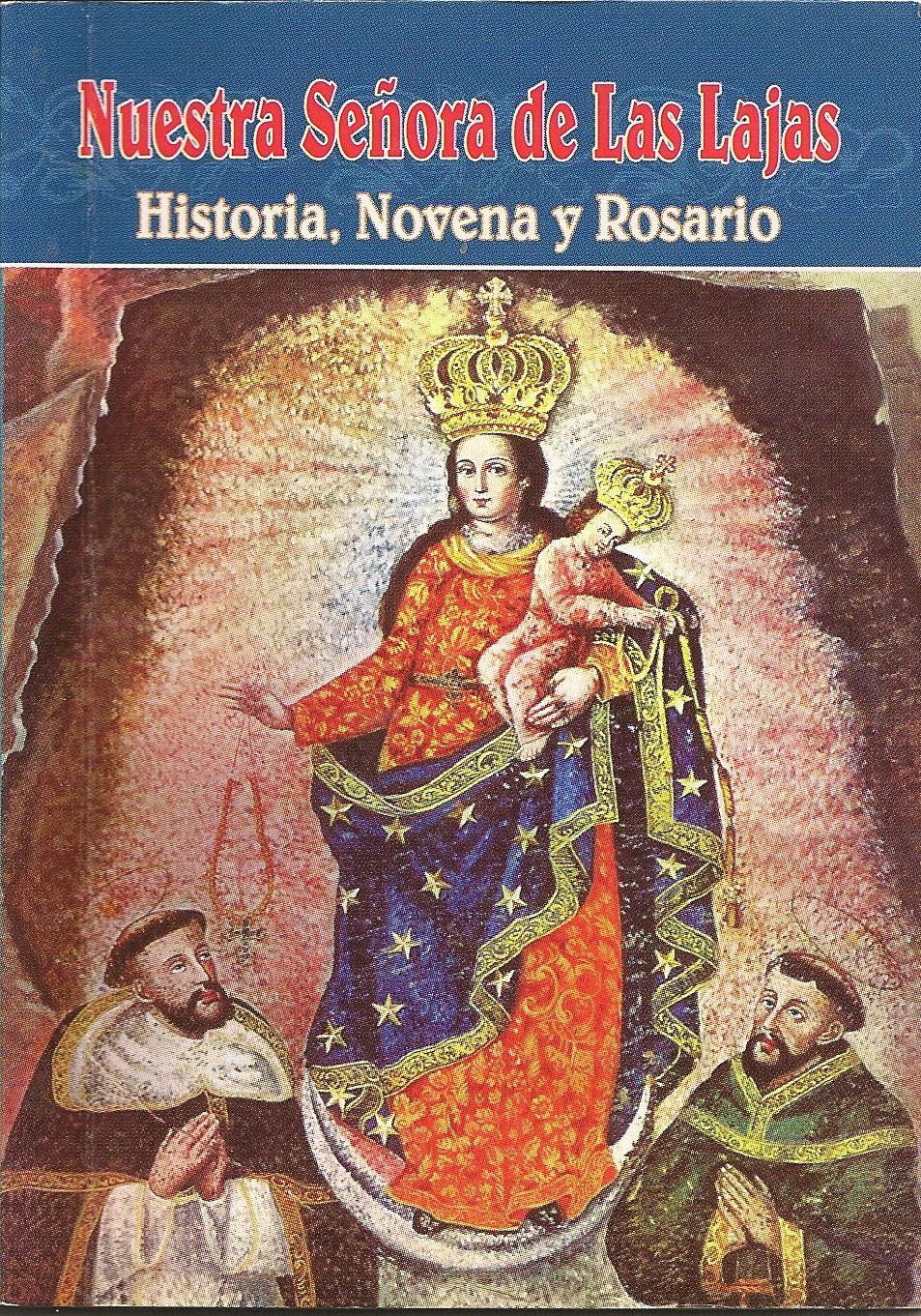

El relato es como sigue: "Refiere la leyenda que una indiecita que se dirigía de Potosí a Ipiales, un día de 1750, junto con su hija Rosa, pasaban por este paraje muy peligroso y una gran tempestad las obligó a buscar refugio en una cueva que allí existía, entró con mucho miedo por las creencias de la presencia del diablo en este lugar, pero mas grande fue su asombro cuando la niña que era sordomuda de nacimiento dijo: 'Mamita, la Mestiza me llama' (este fue el primer milagro de la Virgen).” [Nuestra Senora de Las Lajas, Historia, Novena y Rosario - booklet sold at the gift shop]

The story is as follows: "Referring to legend, an Indian lady who was going from Potosi to Ipiales, one day in 1750, along with her daughter Rosa, passed by this very dangerous place, and a great storm forced them to seek refuge in a nearby cave; she entered in great fear because of her belief in the presence of evil in the cave, but much greater was her astonishment when the little girl who was born deaf said: 'Mommy, the Mestiza (mixed Amerindian and European descent) calls me' (this was the first miracle of the Virgin).”

[based on Google translate]

Riding through the Andes during the daytime was a new adventure for me. The bus ride through the Magdalena valley from Bogota to San Agustin had been during the nighttime, and I was only dimly aware of the Eastern Cordillera (range) and Central Cordillera that we were traveling through on our way through Neiva and numerous small towns. Now, my eyes were riveted to the changing scenery as we left the eastern portion of the Colombia Massif and traversed across the Central Cordillera of the northern Andes. We had left the major Rio Magdalena valley that flowed 1540 kilometers (950 miles) from south to north, and now we were slowly winding our way along a curvy road towards the other major river valley – the Cauca valley. The Cauca River flowed between the mountain ranges of the Cordillera Central and Cordillera Occidental (Western). Both the Rio Magdalena and the Cauca River had their headwaters in the Colombia Massif (also known as Macizo Colombiano).

There was a twelve-year-old boy sitting across the aisle from us. He was traveling alone, and he had his head sticking out of an open window. If there was one thing that made Susie totally uncomfortable, it was cold air. We were traveling across the Andean highlands at about 3,000 meters (9,842 feet). I asked the boy to close the window, but he refused. I tried to explain that “mi hija” (my daughter) was very cold. I didn’t know it at the time, but the boy was nauseous from the rocking motions of the bus as it negotiated the curves in the road. Needless to say, I was completely distracted from the scenery outside the bus, and I was instead involved in a drama with an indigenous boy who refused to close the window. He needed the fresh air to keep from vomiting, and I was trying to act the role of a protective father by looking out for my daughter’s needs. Ultimately, I made the decision to close the window myself to keep my daughter from sneezing her head off. That was a big mistake. The boy vomited all over himself and the floor of the bus.

If there was one thing that I couldn’t stand, it was the sight and smell of vomit. Since I felt it was my fault for closing the window and making the boy throw up, I helped the boy clean up and cover the smelly stuff on the floor. Susie went up to the front to let the bus driver know about the incident. The bus driver told her that there was nothing he could do until they arrived at the town of Isnos. Now we had no choice but to open the window again so we wouldn’t suffocate from the nauseous smell.

After the bus stopped at Isnos, and a lady came on board with a mop and a pail of water to clean up the mess, we all felt much better. I could breathe freely again, without having to hold a handkerchief over my nose. And Susie bundled up with extra clothes that she retrieved from her backpack.

Now I could concentrate on the paramo (open highland) that we were traveling through. The paramo, meaning “desolate territory” in Spanish, is a unique ecological zone mostly found in the higher elevations of the northern Andes. There were plants here that were endemic to the region and grew nowhere else. The spongy, soggy land consisted of vegetation that was dominated by tussock grasses, dwarf shrubs, cushion plants, and a prominent rosette-shrub called Espeletia. The rosette-shape and succulent leaves of the Espeletia plant reminded me of the agave plant.

At the time I didn’t know it, but when we were about two-thirds of the way to Popayan, we actually passed through Purace National Park as the bus meandered across the southern end of the Central Cordillera. This was the park near Popayan that had many sulphur springs, and we would return to the nearby town of Coconuco the next day to enjoy one of the hot springs located several miles west of the park.

After stopping for a short break at the town of Coconuco, the bus trip continued its last leg in a slow descent from the cold highlands of the Central Cordillera to the warm Rio Cauca valley and the city of Popayan. The six hours, 130 km (80 miles) bus ride came to an end – at last.

Susie’s friends were all waiting for her at Teresa’s house. This was Susie’s third visit to Popayan. The first time was with Teresa’s son Gustavo, whom she had met at a school in Costa Rica. He became good friends with Susie and convinced her – when he came to visit his dad in the USA - to travel to Colombia with him. That was when Teresa had high hopes for Susie and her son. The second time was when Susie returned to Colombia and then traveled on to Ecuador to do some volunteer work. This was all part of her Latin studies career that she was pursuing.

The grand welcome at Teresa’s house was accompanied by a sumptuous lunch of frijoles (beans), arroz (rice), ensalada (salad), tomate de arbol juice, and a small plate with fruit. After lunch, Teresa took Susie and me on a walking tour of the city. Every now and then, she would look at Susie and endearingly call her, “Shoozie.” Teresa tried to communicate with me in Spanish, but she soon realized that I had to repeatedly turn to Susie and ask, “What did she say?” In spite of my limited Spanish proficiency, she continued to look at me as she pointed out the places of interest. Her favorite expression, which she used with sheer delight whenever and wherever she could, was: "Chevere!" (super cool, awesome)

“This is our La Catedral,” stated Teresa after we had walked about a mile from her modest two bedroom home on Calle 21. “It is dedicated to Nuestra Senora de la Asuncion.”

I was familiar with Our Lady of the Assumption. That was when the pure Virgin Mary was taken up into the heavens. I was impressed with the pure white façade of the neo-classical building. However, I was sad to see that the cathedral doors were not open today.

“Muy bonita” (very beautiful), I remarked, drawing a smile from Teresa. “Muy blanca” (very white). I glanced up at the two white statues that stood on the upper level above the entrance. I immediately thought of the two figures usually placed on basilicas: St. Peter and St. Paul.

“Popayan – Ciudad Blanca,” said Teresa, saying it slow enough so I could understand that Popayan was called the White City.

My thoughts associated the image of a white city with the pearly white city in the Bible. It was an image that my dearly departed Christian mother had a vision of during her lifetime – an image of a holy city descending from heaven. It was an image that was vividly portrayed in the Bible as a city “prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.” (Rev. 21:1-2)

The vision in my mind of an ideal city, an earthly paradise, came to an abrupt end when Teresa announced, “This is our Clock Tower.” She requested that I take a picture of Susie and her standing in front of the very tall white landmark that stood majestically like a giant guard to the right of the cathedral.

“Now we can go to our central square,” said Teresa as she led us across the street to Parque de Caldas. This was the place where the people of the city congregated for multiple reasons: social, commercial, spiritual, and political. A group with placards seemed to rally around their prospective political leader. Elections for president were approaching. I walked up to the statue that stood on a pedestal in the center of the park. It was a statue of Popayan’s famous martyr-scientist, Francisco Jose de Caldas (1768-1816). The plaque on the pedestal called him: “Al Sabio” (the wise) and “martir de la independencia nacional la patria agradecida” (a martyr for national independence, the grateful country).

Teresa was so happy to see Susie again – and to finally meet her father – that she wanted to take a picture with her at almost every place that we visited. I was glad to grant her requests.

On one of the whitewashed buildings that we passed on our leisurely walk to the next attraction, I noticed a large plaque that said, “Himno a Popayan.” Teresa noticed that I was reading the words of the city hymn. She stopped at the commemorative inscription and sang the hymn in her semi-melodic alto voice:

You Tube: Popayan Hymn, sung in Spanish

Words to Himno a Popayan

Popayán eres madre fecunda

de la patria gestada con luz

Torres, Caldas te dieron su sangre

que hoy abrazan la gloria y la cruz.

Salve villa del genio y procera

noble verso inspiraste sin par

pues tus bardos con lira cimera

fueron cantos del amor filial.

A tí fama vestal de la patria

decorada con blanco de paz

te adormece gentil serenata

y las aves despiertan tu faz.

Viejos fastos proclaman señora

arte y ciencia y guerra y blasón

tu heroísmo traspasa la historia

eres gesta y sublime oblación.

[Letra: Dr. Benjamin Iragorri D.

Música: Luis A. Diago]

Popoyan, you are the fertile mother

Of the country gestated with light.

Torres and Caldas gave you their blood

That today embraces the glory and the cross.

Save the village of Genius and Progress.

You inspired unparalleled noble verses;

Your bards’ greatest music

Were songs of filial love.

The vestal fame of the fatherland,

Decorated you with the white of peace.

It lulls you with a gentle serenade;

The birds wake up your face.

Old annals proclaim the Lady of

Art and science and war and heraldry;

Your heroism transcends history.

You are an epic and sublime sacrifice.

[translated by Susie Wigowsky]

As we continued walking past the white colonial buildings, I noticed the rear window of a car displaying a large picture of Mockus for President. Below the picture of the bearded young man was the slogan: “Partido Verde - Con Educacion Todo Se Puede” (Green Party – With Education Everything is Possible). He seemed to be the hope of the young people in the country.

“We are standing on top of an ancient pre-Hispanic pyramid,” said Teresa when we reached the top and stood admiring the panoramic view of the entire city of Popayan.

Later I learned that the truncated pyramid was built and used as a ceremonial center sometime between 500-1600 B.C. By the time the Spanish arrived in the area in 1535, the pyramid had already been abandoned for some time. I imagined a time when the chiefs ruled their communities, a time when the Paez and Guambianos groups came down from their surrounding communities in the mountainous regions to the centrally-located marketplace and ceremonial center in the Cauca River valley. I visualized a pyramid built on the east side of a large area overlooking the Cauca River valley. The indigenous people would look toward the rising sun when they gathered at the plaza in front of the pyramid. And the chief would stand like a sun-god on top of the pyramid.

As I stood on top of the pyramid-hill, I tried to locate the landmarks of the city. I was able to see the great white dome of the cathedral that rose 40 meters (131 feet) above the surrounding buildings in the city center. On the horizon towards the west, I could see the outline of the Cordillera Occidental (western range). I was trying to locate the Cauca River as it flowed from east to west on the northern border of Popayan, but I was only able to see what looked like the green banks of the river as it flowed westward and then turned northward on its long journey to merge with the Magdalena River before they both emptied into the Caribbean Sea. I thought it was appropriate that the origin of Popayan’s name was from the Quechua word “Pampayan” (Pampa=valley, Yan=river). Popayan was the place where the Cauca River valley had its nearby origin in the Central Cordillera of the Colombian Massif.

Near the pyramid-hill was another hill called the Hill of Belen (Bethlehem). We walked a short distance southeast of the pyramid on a road of paved stone that curved past the stations of the cross up to the white church on top of the hill. I stopped at one of the Via Crucis (Way of the Cross) representations. It showed the Son of Man with a symbolic representation of the cross anchored to his back, and he was teaching two women (the one on his left side had a child in her hands); a devotee on his right side seemed to be listening to every word that proceeded out of the mouth of the Master. It appeared as if the Son of Man was sharing his vision of the upcoming crucifixion and resurrection with his followers.

The final fourteen stone steps up to the platform on which the Capilla de Belen (Belen Chapel) had been built seemed to resemble the steps of a pyramid. A Latin cross made of quarry stone was raised up on a pedestal to the right of the church. The bell tower behind the entrance had three bells of different sizes, and on top of the tower was a unique lightning rod arrangement of a rooster (symbol of the resurrection) standing on a directional arrow that was surmounted by a protective cross.

Inside the chapel was the same El Senor Caido (the Fallen Man) that I had seen in the Montserrat Church on the hill above the city of Bogota. This was the image of the suffering Man of Sorrows that portrayed the agony he underwent on his way to the cross. The vivid image behind the altar epitomized the three times he fell: the first time (station 3) was prior to the moment when he encountered his Mother; the second time (station 7) was when he met the daughters of Jerusalem and told them not to weep for him; and the third time (station 9) was before he was crucified.

Behind the Fallen Man was a corridor that led to the realistic sacred statue of the patron saint of the city – Santo Ecce Homo (Behold the Man). The life-size seated figure was covered in blood, and the wounds showed where he had been beaten. His hands were tied together with rope, and in his right hand was a scepter made of bamboo. A crown of thorns was affixed to his head. The figure reflected the scene from the Bible where the Roman governor Pontius Pilate presented the scourged Son of Man to a hostile crowd and said, “Behold the Man.” (John 19:5) Beside the sacred statue was a vertical scroll-like cloth that appeared to have the image of Jesus on the Shroud of Turin imprinted on it. Upon the cloth were the following words of a prayer:

“Plegaria a la milagrosa imagen del Santo Ecce-Homo”

(Prayer to the miraculous image of the Holy One Ecce Homo, Behold the Man)

Deten, Oh Dios Benigno! tu azote poderoso

Y calma bondadoso tu justa indignacion;

Perdonanos y olvida que te hemos ofendido

Y que hemos afligido tu amante Corazon.

Acuerdate que siempre que te hemos invocado

Sestigna se ha mostrado tu soberana faz;

No nos niegues ahora tu gracia y tus favores,

Suspende tus rigors, concedenos la paz.

Acuerdate que en un tiempo, Senor Omnipotente

nuestra plegaria ardiente tu compasion movio.

Acuerdate que entonces tu diestra poderosa

tendiste, la espantosa borrasca calmo.

Susie tried to translate at least a couple of the stanzas of the prayer:

Stop, O Benign God your powerful scourge,

And calm your righteous indignation;

Forgive us and forget that we have offended you

And that we have grieved your loving heart.

Remember that whenever you have been invoked

You have shown us your sovereign face;

Do not now deny us your grace and your favors,

Suspend your rigors, grant us peace.

Remember that at one time, Lord Almighty,

our ardent prayer moved your compassion.

Remember that then your powerful right hand

calmed the fearful storm.

There was more to the prayer, but the supplications seemed to be repetitive. A simple prayer would have sufficed. It seemed that the prayer was measured not by its brevity, but by its longevity. It reminded me of the prayers of my father, whose petitions to the Almighty seemed to be endless.

At the inconspicuous end of the corridor was a small shrine-like diorama of the Holy Family attached to the wall. Upon closer inspection, this was not the traditional family of Galilee in Jewish garb. The Holy Family of Palestine had been transformed into the Holy Family of Spain, complete with Spanish clothing. Mary and the Child were sitting majestically in a royal chair with a circular silver radiance behind them.

The Iglesia de Santo Domingo that we visited in the historical city center had some notable stonework around its doorway. There were numerous symbolic floral shapes, cross shapes, sun designs, and exotic geometric configurations. The stone arch above the solid ten-foot doors had a different symbol on each separate stone. The thought occurred to me that some of these stones might have once belonged to the nearby pyramid. It was not unusual for stones to be taken from pyramids to build churches; sometimes the church was built right on top of the sacred pyramid. I was surprised that the truncated pyramid at El Morro de Tulcan didn’t have a church on top of it. Instead, the conquistador horseman desecrated the sacred grounds of the indigenous temple that most probably had also served as a sacred burial place.

There was a mass being conducted inside the Santo Domingo church. We entered reverently to watch and listen. I was curious to see the image of the Virgin Mary behind the altar.

“That’s Nuestra Senora del Rosario,” explained Teresa when we approached the front and sat in an empty pew. Our Lady of the Rosary was a popular depiction of the Virgin Mary with her devotional prayer beads (the rosary). The rosary was a vital part of the devotional life, where the meditations on the life of Mary, and the mysteries of the rosary, gave birth to a vision of the Christ life.

There is no telling who you will meet on the streets of any town or city, especially when you walk out of a church. It seems that the needy people know that a merciful hand is most likely to be extended at the threshold of a religious establishment. So they will congregate in the courtyard or at the doorstep of a church and ask for alms. The street beggar who approached me had fallen on hard times. His disheveled appearance, ragged clothes, and two sacks of necessities that he carried on his shoulders told me that this man needed a helping hand. As I searched my pockets for some coins to give him, I thought of the image of the Fallen Man that I had seen at the Belen Chapel. I also heard the words of the Master say, “Inasmuch as you do it unto one of the least of these my brethren, you do it unto me.” Beneath the exterior appearance of the street beggar was a divine soul that desired to be recognized. “Behold the Man” was a corollary of “Behold the Soul.” The man thanked me as I placed a handful of coins into his outstretched hand.

Teresa and Susie thought this would be a good time to take a break. They wanted to rest their aching feet at Parque Caldas. I still wanted to explore the historic downtown area. I told them I’d meet them in the park in half an hour. I loved to walk around and just look at the colonial architecture – and poke my head into any open church.

I don’t remember which church I had walked into, but I was awestruck by a metallic art work representing the Queen of heaven and earth. She was simultaneously standing on a crescent moon and an earth sphere. She was wearing a starry robe, and a metallic oval aureole gloriously emanated from her being. And she had the wings of an angel. I was enraptured by the comprehensive imagery and symbolism embodied in the celestial being. I saw syncretic elements of Pachamama (Earth Mother) and the Virgin Mary blended artistically into the sacred statue.

A block away from the central square, I encountered the Greek version of the various attributes of Mother Earth (Gaia). On top of the Teatro Municipal Guillermo Valencia building stood the nine muses that sprang from the union of Ouranus (Father Sky) and Gaia (Mother Earth). The white statues of the muses were bathed in a rosy color from the rays of the setting sun. I noticed that the nine muses were depicted with the emblems of their creative arts: Calliope (epic poetry, writing tablet), Clio (history, scrolls), Erato (love poetry, kithern), Euterpe (music, flute), Melpomene (tragedy, tragic mask), Polyhymnia (sacred poetry, veil), Terpsichore (dance, lyre), Thalia (comedy, comic mask), and Urania (astronomy, globe).

When I returned to the park, Teresa told us that she had time to show us only one more attraction. It was starting to darken, and she didn’t want to walk home in the dark. She was looking out for our safety, especially since we were foreigners. In short, she didn’t want to take any chances.

The last attraction was the Puente del Humilladero, a bridge that crossed a small stream called Rio Molino. The lights of the city were starting to turn on one by one, and the city seemed to be painted in a glowing hue. A block before the bridge, I spotted the pyramid-hill (El Cerro de Tulcan). I noticed the pyramid shape, and I thought of the pyramid of Chichen Itza that I had climbed. I wondered if this pyramid in Popayan also had 91 steps going up to the temple on top.

The Humilladero bridge was constructed in the old Roman style with 12 arches. It was 178 meters (584 feet) long. As we walked on part of the bridge that connected the historic center with the north zone of Popayan, Teresa told us that the bridge resembled an old Roman-style aqueduct that existed in partial ruin near the Cerro de Tulcan.

Teresa kept an eye on us as she scurried through the calles (streets) and carreras (avenues) back to her humble abode. There was a surprise waiting for us at her house. The surprise came in the form of a four-year-old boy named Lucas. Not only was the boy precocious, he also seemed to have the heart and intuitive mind of a spiritual child. That’s why I eventually started referring to him as El Nino (the Child), which in religious circles was a reference to the Divine Child. One anecdotal example should suffice: When we were sitting at the dinner table and savoring the meal, Lucas was curious to know why Susie and I didn’t eat meat. Susie tried to explain to him that eating meat meant taking the life of an animal. Lucas remarked: “You must be friends of animals.” The innocence and perceptiveness exhibited in that statement reminded me of St. Francis of Assisi and his Canticle to all of God’s creatures, whom he treated as brothers and sisters.

Susie and Lucas struck up a friendship that lasted for the duration of our time in Popayan. It matured into a little boy’s infatuation with a pretty young lady when we traveled the next day to the hot springs near Coconuco. That’s when Susie told me the rest of the story about the semi-orphan boy. He had lost his father – who was related to Gustavo’s father’s side of the family – in a shooting incident. So now he lived with his mother, and sometimes with Teresa, who took care of him when his mother worked to support themselves. Lucas often had nightmares of his father being shot. When he had one of those nightmares as his head slumbered on Susie’s shoulder during the trip up to Coconuco, Susie tried to console him. There was a sweet nature within that boy, and he seemed to connect with the invisible world through the memory of his departed father.

When we reached the hot springs that were located near the south boundary of Purace National Park, Susie became a natural baby-sitter for Lucas. Teresa was relieved of that responsibility, and she took full advantage of it. In fact, the party atmosphere was already in full swing for her as soon as we started our 30 kilometers (18 miles) trip to Coconuco. The radio was turned up, and Teresa was singing and gyrating to the music in the front seat – much to the delight of the middle-aged driver whom we had hired for the day.

The name of the hot springs was aptly named Aguas Hirviendas (Boiling Water). There were three large pools with varying degrees of temperature, and five personal-sized ones. We tried each one of them. Susie and I watched out for Lucas, while Teresa and the driver shared a beer beside the pool. Lucas wanted to run on the wet concrete, and we had to slow down the enthusiastic, playful boy. Soon he was making friends with the other children at the slide pool.

I was impressed with the well-developed hot springs area. I was most impressed by a partially-opened volcanic sulphur vent, where the bubbling, geothermally heated groundwater from the earth’s crust reached a temperature of 90 degrees Celsius (194 degrees Fahrenheit). The hot springs area even had chairs and tables set up for people to enjoy a picnic. Teresa, of course, had prepared a lot of food for us to enjoy after we had spent several hours soaking our bodies in the various pools.

There was a tall black man whom I befriended when I found out he could speak English. He told me he was a teacher, and today was Teacher Appreciation Day in Colombia. Being a retired teacher, I was amazed to hear of such an honorable respect for teachers. In the United States we had days without students called workshop days, where we went to school or conference centers to learn new skills or techniques for use in the classroom. We even had a Teacher Appreciation Week. But an official holiday without students or school was not part of our contract.

“Here, in Colombia,” said Williamson, the tall black man who looked like a giant when I stood next to him, “we are honored throughout the country with a special day. No school, just rest and relaxation. That’s why we came here as a group to the hot springs.”

We compared notes about the two educational systems. It seemed that educational systems varied from country to country, but teachers everywhere were still the ones held ultimately responsible for the behavior and education of the students.

Teresa wanted me to take another picture of her and Susie together – this time striking a pose at the hot springs shower area.

When we left the hot springs, I asked the driver to stop at a scenic place. I wanted to take a picture of the volcano that towered in the distance. I didn’t know if it was the highest active volcano in the area – Purace Volcano at 4,580 meters (15,030 feet) – or if it was one in a chain of six inactive volcanoes in Purace National Park. The thought of volcanoes reminded me of the awesome natural forces moving directly beneath the ground on which we lived.

Back in Popayan, a student named Oliver, who was a boarder at Teresa’s house, told us that there was a special night of music and dancing at the Andina Pena Bar. I was going to experience the night life of Popayan. In the meantime, Teresa put on some of her favorite music for me to listen to while dinner was being prepared. The songs of Juan Gabriel were her favorite. She would sing-a-long soulfully with Juan whenever she walked into the family room where I was sitting. Pretty soon I was humming along with the music. One plaintive song touched my heart and soul, and I asked Teresa to play it several times for me. Then I asked Susie to translate the words for me. The name of the song was Con Tu Amor (With Your Love).

Yo estaba solo

vivia muy triste

creia que nunca iba a encontrar un amor

hasta que llegastes

Se fueron mis penas

y con tu cariño empeze

a olvidar el dolor

Yo esta solo

tan solo soñaba

creia que todos mis sueños

estaban tan lejos de ti

hasta que llegastes

Haaa

se fueron mis penas

y con tu cariño empez

a olvidar, y a olvidar, y a olvidar

mi dolor

Con tu amor

se fueron mis penas

y llego la felicidad

gracias a ti

no ciento tristezas

ni dolor

hoy soy muy feliz

hoy soy muy feliz

con tu amor.

I was alone, was very sad, and believed that I never was going to find love - until you arrived.

They were my sorrows, and with your affection I began to forget the pain.

I was alone, so alone, and I dreamed, I believed that all my dreams were so far from you - until you arrived.

Haaa - my sorrows left, and with your affection I began to forget, and to forget, and to forget my pain.

With your love my sorrows left, and happiness came, thanks to you there is no more sadness or pain.

I am very happy today. I am very happy today with your love.

The spiritual quality of the song Con Tu Amor reverberated in my mind for a long time. The music and words followed me to the Andina Pena Bar that night as I reflected on the dual message inherent in a song like that – romantic love and spiritual love.

The spiritual quality of the song Con Tu Amor reverberated in my mind for a long time. The music and words followed me to the Andina Pena Bar that night as I reflected on the dual message inherent in a song like that – romantic love and spiritual love.

When we arrived at the Andina Pena Bar, I was captivated by the Lady of Machu Picchu mural painted on the wall to the right of the entrance door. Two figures were sitting on the floor, whom I thought were the legendary Manco Kapac and Mama Ocllo, the first human beings – the Inka Adam and Eve. One giant figure stood to the right of the entrance, and I recognized him as the creator god Viracocha. However, it was the mural of Machu Picchu with a red sun to the left and a beautiful Andean woman to the right that caused me to stop and contemplate the vision of a young Pachamama that I was viewing for the first time. Machu Picchu – one of the new wonders of the world – was the climax of our Inka pilgrimage, and now I felt that the Lady of Machu Picchu was guiding our footsteps towards that culminating experience.

I followed Teresa, Oliver, and Susie through the threshold into a world of Andean music and dancing. It was a throbbing beat of the heart, and I watched the movements of the dancers on the dance floor as if they were movements of a drama from some ancient Andean mystery play. There was one couple who was especially fun to watch since they appeared to be semi-professional dancers. However, Teresa was not content to just watch. She kept insisting that I join her on the dance floor. When Oliver asked the semi-professional dancer to dance with him, Teresa grabbed my hand and pulled me out on the dance floor to dance with her. I couldn’t say no to the dance of life – I had to join in the dance.

As I started to move around the dance floor with Teresa, I got closer to the large panoramic mural that served as a backdrop for the dance hall. The central imagery of the Andean landscape was of Pachamama (Mother Nature) and a child whom she was holding to her breast. This scene epitomized the ultimate love and affection of a mother for her child. ‘What a beautiful picture!’ I thought as I continued to embrace the entire ambiance of dancing in Pachamama’s world.

The next morning we said good-bye to Teresa and Popayan (the White City). We were on our way to Ipiales, where the worship of the Mother at the Sanctuary of Las Lajas was incomparable to anything I had seen before. Except for, perhaps, my experience with Santa Maria (Virgin of Guadalupe) in Mexico City years ago.

The first view of the Sanctuary of Las Lajas (the Rocks) was from a high scenic overlook on the road that led from the nearby town (7 km) of Ipiales. We hired a taxi from the bus station because we wanted to return to the station before sun down for a bus ride from the border town of Ipiales to Quito, Ecuador. The taxi driver would wait for us while we toured the sacred site.

Susie had been to the sanctuary before, and she knew I would enjoy seeing it. She was right. The sight of the neo-Gothic architecture made me think that I was entering a fairy tale land, a fantasy of my dreams. I thought the sanctuary was emerging right out of a sheer cliff. The soaring spires seemed to elevate it right into the heavens, and the bridge across the deep gorge of the Guaitara River seemed to anchor the edifice to the other side. I couldn’t wait to walk down the long walkway to see what was inside that magnificent building.

Two dressed-up llamas with saddles looked curiously at us as we walked past. Their master was in the business of making some money from the multitude of tourists who visited the sanctuary. We walked past without having our pictures taken with the llamas. We had a limited time to visit the main attraction. We also walked past the favorite local dish, known as cuy or fried guinea pig. We were friends of animals, and we were not enticed to taste the flesh of those little creatures that Susie used to have as pets.

High on a hill across from the Sanctuary of Las Lajas stood the guardian and caretaker who watched over the sacred building, the sacred river that flowed under the sacred bridge, and the sacred image of the Nuestra Senora de Las Lajas that was embedded in the sacred rock inside the sanctuary. He was the archangel Michael (which in Hebrew means “who is like God”). He was the great general of the divine army that defeated the enemy – Lucifer and the fallen angels – and he was the chivalric angelic being with wings, sword and shield who defeated the dragon. His heroic conquest of the dragon was what I saw as I looked at the towering white statue of Michael with his foot on the many-headed dragon and his sword raised to the sky. To me this was another symbolic representation of the serpent (dragon) power and the conquest of that (kundalini) power for the good of mankind. I also remembered that Michael was one of the four archangels who was the watcher or guardian of the eastern section of the heavens, which marked the autumnal equinox (also known as Michaelmas in Christian terminology).

As we came closer to the sanctuary, there were two statues that were erected to commemorate the great story associated with the sanctuary. One of the statues was of Manuel de Rivera, a blind man who went throughout the countryside begging for money to buy materials so that a shrine could be built to protect the image of Our Lady of Las Lajas (the Rocks). A plaque on a pedestal under his bronze statue told the story:

“En 1765 el ciego ipialeno Manuel de Rivera, en agradacimiento a la curacion obtenida, hizo voto a la Sma. Virgen de las Lajas de dedicarse a pedir limosna, para que fuese sustituida por una capilla de cal y piedra, la pajiza existente hasta entonces. En sus andanzas por el Ecuador y otros pueblos reunion a tal fin 388 pesos con 7 reales.”

In 1765 the blind man from Ipiales, Manuel of Rivera, in gratitude for a healing, made a vow to the Blessed Virgin of Las Lajas to ask for charity to replace a straw thatched building by a chapel of lime and stone. In his journey through Ecuador and other towns, he collected for that purpose 388 pesos and 7 reales.

The other statue was of the Mestiza (of mixed race) woman named Maria Mueses de Quinones and her deaf-mute daughter Rosa. The bronze statue of the bare-footed woman carrying her daughter on her back depicted the miraculous moment when the deaf-mute pointed to the image in the grotto and said the Lady was calling her. The woman was standing on a pile of rocks, and underneath was a white plaque with a dated inscription:

“Refiere la tradicion que al acercarse Maria Mueses de Quinones a la gruta, de regreso de Ipiales, oyo exclamar a su pequena hija Rosa: Mamita La Mestiza me llama.” IX – 2 – MCMXLI

Refers to the tradition that upon approaching the cavern, Maria Mueses of Quinones, upon her return to Ipiales, she heard her little daughter Rosa exclaim: “Mama, the Mestiza (of mixed race) is calling me...". (9th of Feb. 1941)

According to the legendary encounter, Maria was traveling with her daughter Rosa from her hometown of Potosi to the western village of Ipiales, which was 10 kilometers (6 miles) away. She was caught in a storm as she was walking on a trail beside the precarious gorge along the Guaitara River. She looked for shelter in the nearby grotto, even though she had heard rumors that the cave was haunted. The child Rosa went into the cave first, and she immediately informed her mother that the Mestizo (mixed heritage) lady inside spoke to her. The mother did not see anyone inside, and she decided to leave without investigating her daughter’s claim. A few days later, the daughter Rosa disappeared, and the mother guessed that she probably heard the call of the Lady, again. When the mother returned to the grotto, she found her eight-year-old daughter playing with the Divine Child. The Lady of Las Lajas revealed herself to both Maria and Rosa.

The story unfolded in other ways, including a miraculous resurrection of Rosa’s body when she suddenly died of a severe illness. Afterwards, the village people went to the grotto to find out about the miracle-working Lady of Las Lajas. That was when they discovered the marvelous picture of the Lady of Las Lajas with the Divine Child embedded in the Rocks. Various versions of the story were told – including one where the mother is named Juana (“God’s Grace”) and she saw the luminous figure of the Virgin emanating from the rock while she was cutting wood in the area – but in all of them the Mestizo mother Maria and her daughter Rosa, and their encounter with the Mestizo Mother of the Divine Child, were at the center of the story. The mixed race of people in Latin America now had their own Mestizo Mother with whom they could identify.

We were almost at the building that had been declared a basilica in 1954. Part of the building was presently surrounded by unsightly yellow scaffolding. They must have been refurbishing the building to make it more attractive for the tourists. Toward the end of the walkway we read some of the numerous plaques that were attached to the wall of miracles. The short statements of thanksgiving on the plaques enumerated the many miracles that were attributed to the wonder-working power of the Lady of Las Lajas. One of the plaques said:

Ante el Altar de la Mestiza, y el intrepido Guaitara: Un Dios le Pague. Aqui Empieza Colombia. Edcalher, 2009

Before the Altar of the racially mixed one, and the intrepid Guaitara (River): God Pays him. Here Begins Colombia. Edcalher, 2009

The side of the building had several doorways. The first one had wood relief carvings that depicted the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. Above the double doors was a very colorful semi-oval mural depicting the new Eve – the Mother of Humanity – in the form of Mother Mary holding her Divine Child. The image of the Mother and Child were enclosed within an elongated oval aureole, and her feet were standing on a circular shape with a crescent that seemed to symbolize both the sun and the moon. To the right of the divine image was St. Francis kneeling on a rock ledge and receiving the Franciscan cord of three knots (representing the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience) from the Divine Child; to the left was St. Dominic kneeling on a rock ledge and receiving the holy rosary from the Mother. Indigenous people stood below with their hands uplifted in adoration of the vision of the Lady of Las Lajas. The mural seemed to depict the part of the story where the village people came to the grotto to see the inexplicable wonder of the picture (or painting) on the rocks (las lajas). The other doorway depicted what appeared to be the loaves and fishes that were fed to the thousands of people who came to hear the teachings of the Master.

The view of the waterfall, the bridge, and the façade of the basilica appeared simultaneously. The view was majestic and overwhelming – absolutely stupendous. The long thin ribbon of white foamy water coming out of the steep hillside formed a wonderful waterfall that plunged 100 feet down the cliff to join the river below. The neo-Gothic basilica with the three entrances, the towering spires, and the gray stones with white embellishments provided a picture of heavenly beauty. There seemed to be statues of angels everywhere – on top of the pinnacles were white angels with trumpets, and the bridge was lined with five white angels on each side.

Before we walked through the central entrance past the white statue of a meditative winged-angel, I glanced up at the colorful semi-oval mural that covered the tympanum above the front entrance. Mother Mary was sitting on a rock with a naked Divine Child on her lap. Two adoring Marians, a priest and a nun, of the Dominican order in their black and white habits, were receiving a rosary from the Mother and Child. After I walked through the threshold and entered the sanctuary, I turned around to look up at the light streaming through the multi-colored stained-glass of the rose window, which had the monogram letter M for Mary at the center and 16 rays emanating from the center and 16 quatrefoils (four leaves) with images of saints inside making up the outer circle. The entire design was a 32-point compass rose, which seemed to expand to all ends of the universe. Below the mandala-like rose window was a painting of the coronation of Mary by her son, Jesus.

A wedding service had just ended, and the entire bridal party was still milling around at the front of the sanctuary. We slowly made our way towards the sacred image of Our Lady of Las Rajas (the Rocks), which served as the high altar of the sanctuary – the central focal point of adoration and worship. The monolithic monument seemed to stand about 10 feet tall, and it was surrounded by a shrine with two marble pillars and golden letters stating, “Ave Gratia Plena” (Hail Mary Full of Grace). The life-sized images of Mother Mary, Divine Child, Saint Francis, and Saint Dominic appeared to be embedded in the surface of the rock, almost like holographic images that seemed to have a life of their own within a substance. In short, it seemed to be created by an inner illumination of light that beamed its inner essence to the eye of the beholder. It seemed to be similar in religious iconography to the Veil of Veronica, the Mandylion, and the famous Shroud of Turin. The phrase “akeropita image” (image not made by human hands) seemed to be an apt phrase to explain the mysterious and inexplicable – in human terms.

The majestic image of the Queen of Heaven standing on a crescent moon stirred the heart and soul of the devotee, for whom an explanation was not necessary. The beauty of the image, with the Holy Mother clothed in a red floral dress and a starry robe draped around her shoulders, was something the indigenous people could identify with. The image of the Mother was an expression of their divine spiritual mother – Pachamama. She was the mother of humanity, the mother of nature with all of its life forms, and the eternal feminine whose cosmic nature dwelt in all physical, astral, and spiritual bodies. The Lady of Las Lajas was the manifestation of her mestizo form for the Andean people and the people of Latin America, who were also mostly mestizo (mixed European and Native American heritage).

To the left of the high altar of the Lady of Las Lajas image was a separate nativity scene with the holy family (Mary in a celestial blue robe, Joseph in a royal purple robe, and the Divine Child in swaddling clothes) placed on top of a rock altar. To the right of the high altar was a separate resurrection scene with a diorama of a risen Christ between two Roman soldiers placed on top of a rock altar. The white robed Christ held a banner in his left hand saying, “Resucito Aleluya” (He is Risen, Hallelujah).

There were eight stained-glass windows that portrayed scenes from prominent Marian shrines throughout the world where the Mother Mary had appeared. The first one, Notre Dame (Our Lady) of Lourdes, was an apparition of the Virgin Mary to a 14-year-old peasant girl named Bernadette. This happened in 1858 near the town of Lourdes, France. The scene depicted the Virgin Mary wearing a brown robe with a blue inner garment, and she had a striped yellow and orange aureole around her. There seemed to be a white full moon that served as her halo. The girl Bernadette was kneeling before the apparition, and she had a yellow halo around her head, signifying that she had received the status of a saint.

The second Marian window portrayed the appearance of the Notre Dame de La Salette (Our Lady of La Salette) to two shepherd children, Melanie and Maximin, at a small mountaintop village near Grenoble, France in 1846. The Lady was wearing a golden dress, and a fan-shaped halo surrounded her head.

The third Marian window had the following title under the pastoral scene: “N.S. do Rosario de Fatima” (Our Lady of the Rosary of Fatima). The scene portrayed Our Lady appearing to three shepherd children named Lucia, Jacinta, and Francisco at Fatima, Portugal in 1917. The Lady was wearing a dark brown garment and hooded robe, and a golden halo with 12 stars surrounded her head. The three children were kneeling in adoration.

The fourth Marian window was the one I identified with: Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe. She was the Lady who appeared to a simple indigenous peasant named Juan Diego near Mexico City in 1531. She was the Lady I called to, saying, “Santa Maria, ayuda me” (help me) when two armed robbers stole my wallet and personal belongings in Mexico City. To this day I tell the story of how Santa Maria came to my assistance and the robbers left me alone. I even got them to return my wallet after they took the money out. Later, I visited the icon of the Virgin of Guadalupe at the Basilica of Guadalupe, where I watched the pilgrims to the shrine crawl on their knees the last part of the pilgrimage. Also, I went with a group of teachers to a restaurant in Puebla where the entire story of Juan Diego meeting the Lady was portrayed in several murals. I still think very fondly of her, and I think the appropriate title for her is “Empress of the Americas.”

The fifth Marian window portrayed Nuestra Senora de Chiquinquira (Our Lady of Chiquinquira). Chiquinquira was a small town in the department of Boyaca in Colombia, where the image of the Virgin appeared on a wooden slab to a washerwoman named Maria Cardenas. The window showed the small square-shaped wooden slab with the image of the Mother Mary holding her divine child; also depicted alongside her is the Apostle Andrew with an open book in his right hand and his X-shaped martyr’s cross in his left hand. The indigenous woman shows the image to a child. She expresses the sentiment of her people when she says, “She is the way that leads to Jesus.”

The sixth Marian window told the story of Nuestra Senora del Quinche (Our Lady of Quinche). The image was carved as a wooden sculpture by an artist named Don Diego de Robles in the 16th century. It was an image of the Lady clothed with a luxurious brocade robe, holding a scepter in her right hand and the Divine Child in her left hand. She was the synthesis of the Inca and the Spanish, embodying both the loving nature of Pachamama and the saving grace of the Virgin Mary. The image had previously appeared to people in a cave. When the image-sculpture was transferred to the town of Quinche, northwest of the city of Quito, Ecuador, the Lady became known as Our Lady of Quinche.

The seventh Marian window portrayed the story of the Madonna di Loreto, a town in Italy. The story revolved around Mary’s house in Nazareth, where she was born and raised -- according to tradition. The house was supposedly carried by angels to Italy – according to legend -- to save it from the conquest of Palestine by Islam in the 13th century. The window showed the small house in the left panel, and the cedar statue of a richly adorned Madonna of Loreta in the right panel.

The eighth Marian window showed Our Lady of Zaragoza (of Spain) appearing to Saint James (the Elder) before her Assumption. St. James (also known as Santiago in Spain) was the apostle who – according to tradition – brought Christianity to Spain. The window showed St. James looking up to the Mother of God with the Divine Child on her left arm. All three of them had a golden halo around their head. This was the image that was venerated as the “Mother of the Hispanic People” by Pope John Paul.

I started to walk towards the back of the sanctuary. I still wanted to walk on the bridge and down the path to the waterfall. As I glanced one last time at the rose window, I noticed cherubs (baby angels) in the corners below the window looking towards the sacred image of the Lady of Las Lajas that was impregnated in the sacred rock. The innocence in their faces illustrated the innocence in the faces of the believers who beheld the portrait of the Lady of Las Lajas. It was a suspension of disbelief that allowed the devotee of the Mother Mary (or Pachamama) to see her natural beauty and all-pervading power – even in an imprint in Las Lajas (the Rocks).

The wedding couple, along with the ring boy and flower girl, was also leaving the sanctuary. Man and woman – united in holy matrimony (from mater, mother). Life would continue through the creative aspect of Motherhood – the spiritual aspect of Motherhood being propagated through the divine Mother (Pachamama), and the physical aspect of Motherhood being propagated through the earthly mother (the bride). “Blessed is the fruit of your womb” was the annunciation given to the Virgin Mary at the Vernal Equinox (Feast of the Annunciation in Christian terminology). “Blessed is the fruit of your womb” was the annunciation given to Pachamama (Mother Nature) at the beginning of time. The mysteries of Mother Mary and the mysteries of Pachamama both revealed the mysterious divine aspects and creative power of motherhood.

Susie and I stopped at the gift shop to see what was there. I bought a small booklet about the Nuestra Senora de Las Lajas – Historia, Novena y Rosario. I noticed a curious rendition of the last supper on the rock wall of the gift shop. It only had six disciples, instead of twelve. I wondered if it was an Andean version with a penchant for the symbolic number seven (six disciples and one master).

The view of the basilica from across the river was enchanting, heavenly, and out of this world. It almost seemed as if the entire edifice had been carved out of the rock in the cliff side. To the right of the towering Gothic structure I could see the wall of miracles and the wide staircase that we had descended to reach the glorious sanctuary. We would have to ascend the 266 steps back to the taxi that was waiting for us. In the meantime, we wanted to enjoy the grandeur of the view.

A young couple volunteered to take several pictures of Susie and me in front of the pilgrimage site. They told us that not far from here there was a place where petroglyphs from the Pasto culture could be seen. I thought that perhaps they were the ones who could have produced the image of the earth mother (Pachamama) on the rocks, and later that image was reinterpreted as the image of Mother Mary. After all, the conquest by Spain, and the forced conversion to Catholicism, caused the figure of Virgin Mary to have precedence over the image of Pachamama.

The sun was shining pretty brightly on us, and we knew that it was getting close to the time when we had to leave the beautiful place, which was like a little paradise on earth. There was the beauty of the majestic architecture, and there was the beauty of the river, the gorge, the hills, and the waterfall. The beauty of man’s work in stone and the beauty of Pachamama’s work in natural phenomena were equally impressive.

I took a look at the remarkable bridge that crossed the abyss of the deep gorge. I thought I saw a statue inside a niche between the two arches. I took a picture of the bridge and zoomed in on the picture within the zoom mode of the digital camera. It definitely was a white angelic statue with the words “Ave Maria Gratia Plena” above the niche. They were the same words that were above the 3.2 high and 2.3 meters wide rock slab inside the sanctuary: “Hail Mary Full of Grace.”

I took a look at the basilica through the eyes of the natural landscape as I peered through the feathery flower head plumes of the pampas grass. Then I took a look at the waterfall flowing above Susie’s head, as if it was the water of life coursing through the back of her spine (like the kundalini).

On our way back along the path to the bridge and the basilica, we stopped to pay homage to the little angelic being, who looked like the Divine Child with wings. The little angel was offering us a drink of holy water from the fountain of life. We gladly sipped the water that probably came from the river below.

One last stop – and that was it. I wanted to see the portrayal of the Divine Child – that I had seen in the gift shop – one last time. The androgynous-looking Divine Child was wearing a lavender robe, an elaborate sunburst halo surrounded his red-haired head, and his little hands were raised to the heavens. He was enjoying the beauty of nature as he walked in a field of flowers beside a flowing river. I was not aware of it at the time I took a picture of the Divine Child, but later I noticed a swirling cloud to the right – inside and outside the frame – that appeared to have the head of a Lady also admiring the amazing portrayal of her Son. Was that an apparition? I would like to think so.

After we climbed up the staircase back to the taxi, I saw that the llamas were standing this time. I would have loved to sit in the saddle and take a picture with a llama, but I saw that the taxi driver was waiting impatiently for us. It was time for us to go to the bus station.

As we drove on the night bus to the border of Ecuador, I opened the little booklet of the Nuestra Senora de Las Lajas that I had bought and started to read about the Novena, and the nine day devotions that revealed the mysteries of Mary and Motherhood. The devotion for the eighth day seemed to say it all for me: “Blessed are the eyes which see the things that you see.” (Luke 10:23)